Unidirectional Dataflow for your favourite reactive framework

If you’ve got questions, about SwiftRex or redux and Functional Programming in general, please Join our Slack Channel.

Introduction

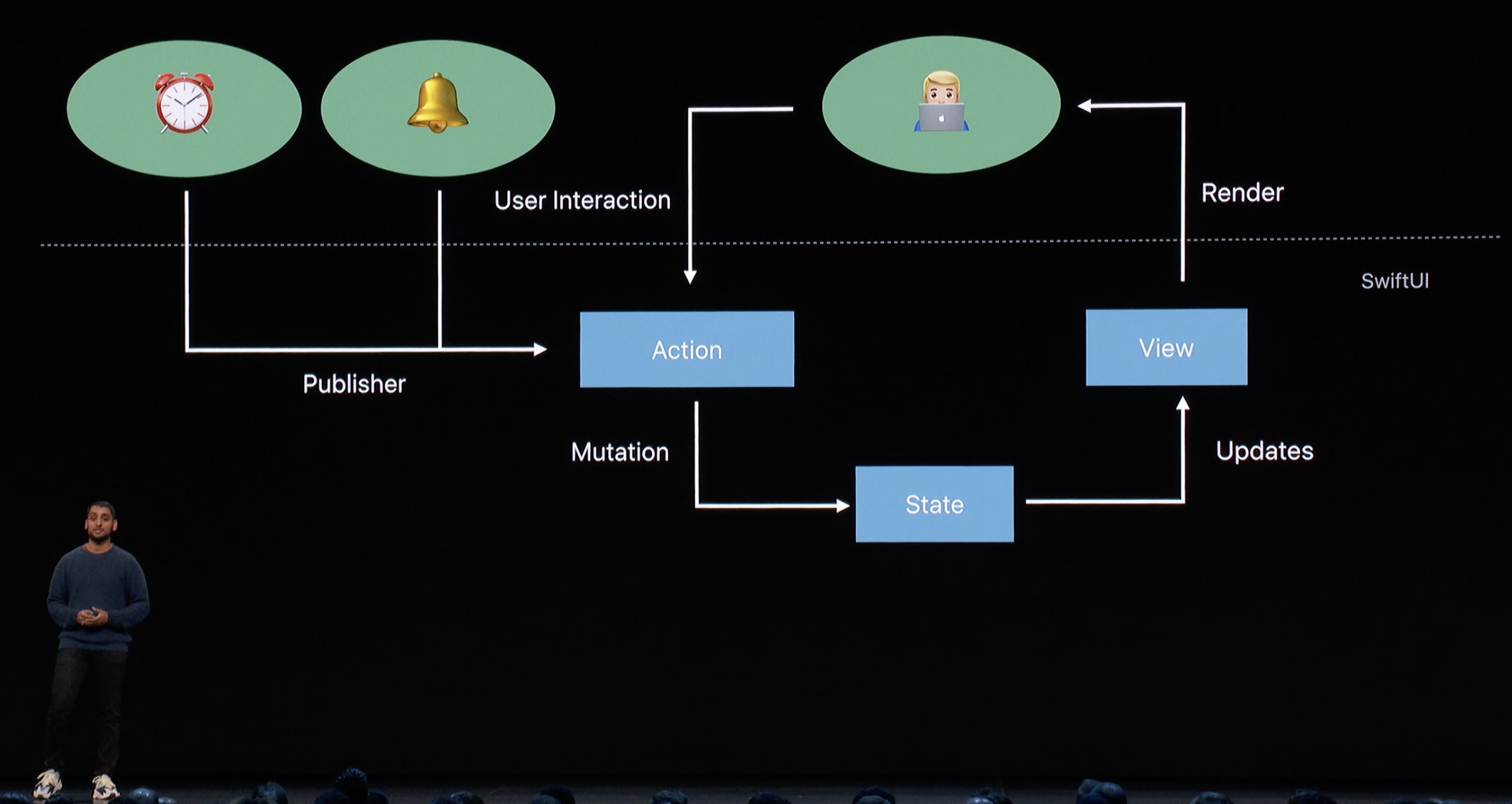

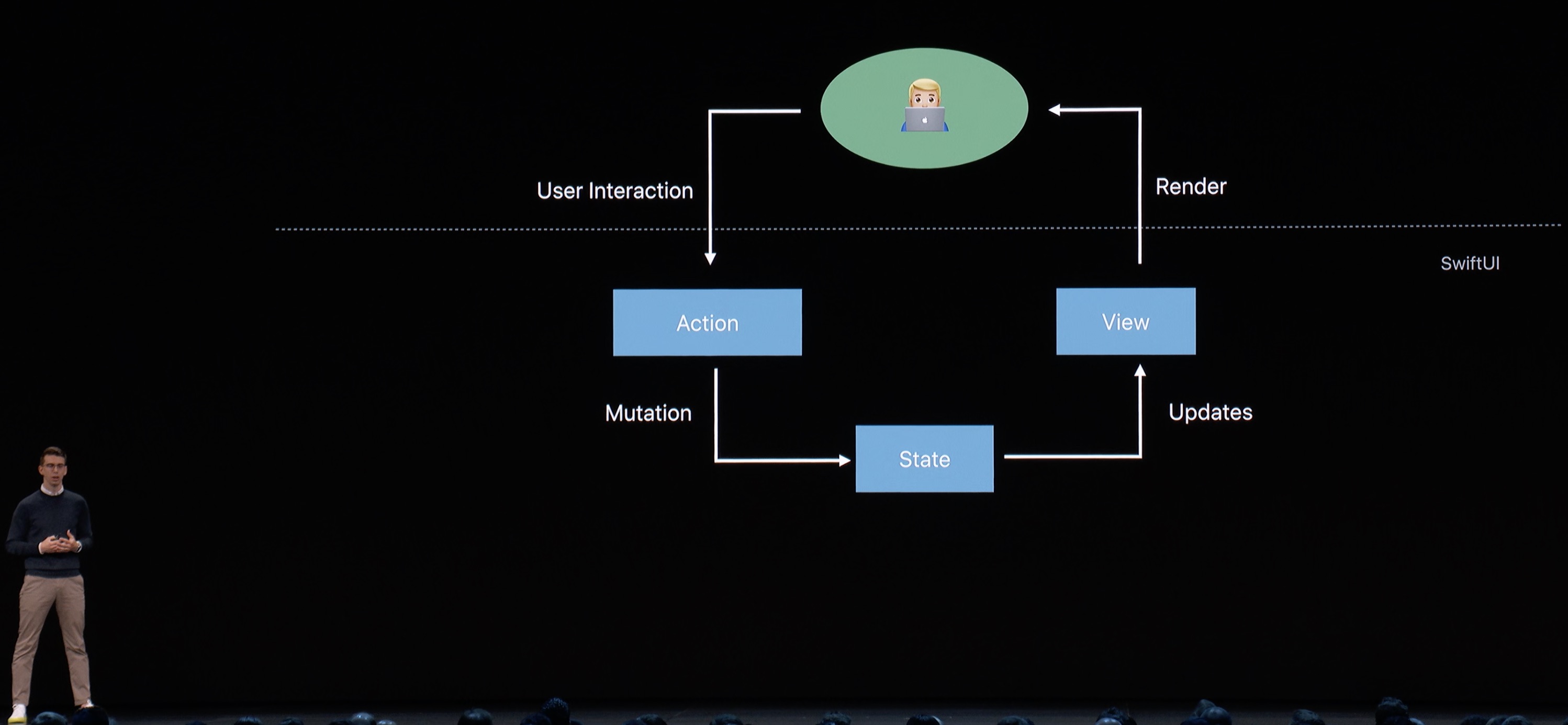

SwiftRex is a framework that combines Unidirectional Dataflow architecture and reactive programming (Combine, RxSwift or ReactiveSwift), providing a central state Store for the whole state of your app, of which your SwiftUI Views or UIViewControllers can observe and react to, as well as dispatching events coming from the user interactions.

This pattern, also known as “Redux”, allows us to rethink our app as a single pure function that receives user events as input and returns UI changes in response. The benefits of this workflow will hopefully become clear soon.

API documentation can be found here.

Quick Guide

In a hurry? Already familiar with other redux implementations?

No problem, we have a TL;DR Quick Guide that shows the minimum you need to know about SwiftRex in a very practical approach.

We still recommend reading the full README for a deeper understanding behind SwiftRex concepts.

Goals

Several architectures and design patterns for mobile development nowadays propose to solve specific issues related to Single Responsibility Principle (such as Massive ViewControllers), or improve testability and dependency management. Other common challenges for mobile developers such as state handling, race conditions, modularization/componentization, thread-safety or dealing properly with UI life-cycle and ownership are less explored but can be equally harmful for an app.

Managing all of these problems may sound like an impossible task that would require lots of patterns and really complex test scenarios. After all, how to to reproduce a rare but critical error that happens only with some of your users but never in developers’ equipment? This can be frustrating and most of us has probably faced such problems from time to time.

That’s the scenario where SwiftRex shines, because it:

enforces the application of Single Responsibility Principle [tap to expand]

Some architectures are very flexible and allow us to add any piece of code anywhere. This should be fine for most small apps developed by only one person, but once the project and the team start to grow, some layers will get really large, holding too much responsibility, implicit side-effects, race conditions and other bugs. In this scenario, testability is also damaged, as is consistency between different parts of the app, so finding and fixing bugs becomes really tricky.

SwiftRex prevents that by having a very strict policy of where the code should be and how limited that layer is, policy that is often enforced by the compiler. Well, this sounds hard and complicated, but in fact it’s easier than traditional patterns, because once you understand this architecture you know exactly what to do, you know exactly where to find some line of code based on its responsibility, you know exactly how to test each component and you understand very well what are the boundaries of each layer.

offers a clear test strategy for each layer (also check TestingExtensions) [tap to expand]

We believe that an architecture must not only be very testable, but also offer a clear guideline of how to test each of its layers. If a layer has only one job, and this job can be verified by assertions of expected outputs based on given input all the times, the tests can be more meaningful and broad, so no regressions are introduced when a new feature is created.

Most layers in SwiftRex architecture will be pure functions, that means all its computation is done solely from the input parameters, and all its results will be exposed on the output, no implicit effect or access to global scope. Testing that won’t require mocks, stubs, dependency injection or any kind of preparation, you call a function with a value, you check the result and that’s it.

This is true for the UI Layer, presentation layer, reducers and state publishers, because this whole chain is a composition of pure functions. The only layer that needs dependency injection, therefore mocks, is the middleware, once it’s the only layer that depends on services and triggers side-effects to the outside world. Luckily because middlewares are composable, we can break them into very small pieces that do only one job, and testing that becomes more pleasant and easy, because instead of mocking hundreds of components you only have to inject one.

We also offer TestingExtensions that allows us to test the whole use case using a DSL syntax that will validate all SwiftRex layers, ensuring that no unexpected side-effect or action happened, and the state was mutated step-by-step as expected. This is a powerful and fun way to test the whole app with few and easy-to-write lines.

isolates all the side-effects in composable/reusable middleware boxes that can’t mutate the state [tap to expand]

If a layer has to handle multiple services at the same time and mutate the state as they asynchronously respond, it’s hard to keep this state consistent and prevent race conditions. It’s also harder to test because one effect can interfere in the other.

Along the years, both Apple and the community created amazing frameworks to access services in the web or network and sensors in the device. Unfortunately some of these frameworks rely on delegate pattern, some use closures/callbacks, some use Notification Center, KVO or reactive streams. Composing this mixture of notification forms will require boolean flags, counters, and other implicit state that will eventually break due to race conditions.

Reactive frameworks help to make this more uniform and composable, especially when used together with their Cocoa extensions, and in fact even Apple realised that and a significant part of WWDC 2019 was focused on demonstrating and fixing this problem, with the help of newly introduced frameworks Combine and SwiftUI.

But composing lots of services in reactive pipelines is not always easy and has its own pitfalls, like full pipeline cancellation because one stream emitted an error, event reentrancy and, last but not least, steep learning curve on mastering the several operators.

SwiftRex uses reactive-programming a lot, and allows you to use it as much as you feel comfortable. However we also offer a more uniform way to compose different services with only 1 data type and 2 operators: middleware, `<>` operator and `lift` operator, all the other operations can be simplified by triggering actions to itself, other middlewares or state reducers. You still have the option to create a larger middleware and handle multiple sources in a traditional reactive-stream fashion, if you like, but this can be overwhelming for un-experienced developers, harder to test and harder to reuse in different apps.

Because this topic is very wide it’s going to be better explained in the Middleware documentation.

minimizes the usage of dependencies on ViewControllers/Presenters/Interactors/SwiftUI Views [tap to expand]

Passing dependencies as you browse your app was never an easy task: ViewControllers initialisers are very tricky, you must always consider when the class is being created from NIB/XIB, programmatically or storyboards, then write the correct init method passing not only all the dependencies this class needs, but also the dependencies needed by its child view controllers and the next view controller that will be pushed when you press a button, so you have to keep sending dozens of dependencies across your views while routing through them. If initialisers are not used but property assignment is preferred, these properties have to be implicit unwrapped, which is not great.

Surely coordinator/wireframe patterns help on that, but somehow you transfer the problems to the routers, that also need to keep asking more dependencies that they actually use, but because the next router will use. You can use a service locator pattern, such as the popular Environment approach, and this is really an easy way to handle the problem. Testing this singleton, however, can be tricky, because, well, it’s a singleton. Also some people don’t like the implicit injection and feel more comfortable adding the explicit dependencies a layer needs.

So it’s impossible to solve this and make everybody happy, right? Well, not really. What if your view controllers only need a single dependency called “Store”, from where it gets the state it needs and to where it dispatches all user events without actually executing any work? In this case, injecting the store is much easier regardless if you use explicit injection or service locator.

Ok, but someone still has to do the work, and this is precisely the job that middlewares execute. In SwiftRex, middlewares should be created in entry-point of an app, right after the dependencies are configured and ready. Then you create all middlewares, injecting whatever they need to perform their work (hopefully not more than 2 dependencies per middleware, so you know they are not holding too many responsibilities). Finally you compose them and start your store. Middlewares can have timers or purely react to actions coming from the UI, but they are the only layer that has side-effects, therefore the only layer that needs services dependencies.

Finally, you can add locale, language and interface traits into your global state, so even if you need to create number and date formatters in your state you still can do it without dependency injection, and even better, react properly when the user decides to change an iOS setting.

detaches state, services, mutation and other side-effects completely from the UI life-cycle and its ownership tree [tap to expand]

UIViewControllers have a very peculiar ownership model: you don’t control it. The view controllers are kept in memory while they are in the navigation stack, or if a tab is presented, or while a modal view is shown, but they can be released at any point, and with it, anything you put the ownership under view controller umbrella. All those [weak self] we’ve been using and loving can actually be weak sometimes, and it’s very easy to not reason about that when we “guard that else return”. Any important task that MUST be completed, regardless of your view being shown or not, should not be under the view controller life-cycle, as the user can easily dismiss your modal or pop your view. SwiftUI that has improved that but it’s still possible to start async tasks from views’ closures, and although now that view is a value-type it’s a bit harder to make those mistakes, it’s still possible.

SwiftRex solves this problem by enforcing that all and every side-effect or async task should be done by the middleware, not the views. And middleware life-cycle is owned by the store, so we shouldn’t expect any unfortunate surprise as long as the store lives while the app lives.

You still can dispatch “viewDidLoad”, “onAppear”, “onDisappear” events from your views, in order to perform task cancellations, so you gain more control, not less.

For more information please check this link

eliminates race conditions [tap to expand]

When an app has to deal with information coming from different services and sources it’s common the need for small boolean flags here and there to check when something has completed or failed. Usually this is due to the fact that some services report back via delegates, some via closures, and several other creative ways. Synchronising these multiple sources by using flags, or mutating the same variables or array from concurrent tasks can lead to really strange bugs and crashes, usually the most difficult sort of bugs to catch, understand and fix.

Dealing with locks and dispatch queues can help on that, but doing this over and over again in a ad-hoc manner is tedious and dangerous, tests must be written that consider all possible paths and timings, and some of these tests will eventually become flaky in case the race condition still exists.

By enforcing all events of the app to go through the same queue which, by the end, mutates uniformly the global state in a consistent manner, SwiftRex will prevent race conditions. First because having middlewares as the only source of side-effects and async tasks will simplify testing for race conditions, especially if you keep them small and focused on a single task. In that case, your responses will come in a queue following a FIFO order and will be handled by all the reducers at once. Second because the reducers are the gatekeepers for state mutation, keeping them free of side-effects is crucial to have a successful and consistent mutation. Last but not least, everything happens in response to actions, and actions can be easily logged in or put in your crash reports, including who dispatched that action, so if you still find a race condition happening you can easily understand what actions are mutating the state and where these actions come from.

allows a more type-safe coding style [tap to expand]

Swift generics are a bit hard to learn, and also are protocols associated types. SwiftRex doesn’t require that you master generics, understand covariance or type-erasure, but more you dive into this world certainly you will write apps that are validated by the compiler and not by unit-tests. Bringing bugs from the runtime to the compile time is a very important goal that we all should embrace as good developers. It’s probably better to struggle Swift type system than checking crash-reports after your app was released to the wild. This is exactly the mindset Swift brought as a static-typed language, a language where even nullability is type-safe, and thanks to Optional

SwiftRex enforces the use of strongly-typed events/actions and state everywhere: store’s action dispatcher, middleware’s action handler, middleware’s action output, reducer’s actions and states inputs and outputs and finally store’s state observation, the whole flow is strongly-typed so the compiler can prevent mistakes or runtime bugs.

Furthermore, Middlewares, Reducers and Store all can be “lifted” from a partial state and action to a global state and action. What does that mean? It means that you can write a strongly-typed module that operates in an specific domain, like network reachability. Your middleware and reducer will “speak” network domain state and actions, things like it’s connected or not, it’s wi-fi or LTE, did change connectivity action, etc. Then you can “lift” these two components - middleware and reducer - to a global state of your app, by providing two map functions: one for lifting the state and the other for lifting the action. Thanks to generics, this whole operation is completely type-safe. The same can be done by “deriving” a store projection from the main store. A store projection implements the two methods that a Store must have (input action and output state), but instead of being a real store it only projects the global state and actions into more localised domain, that means, view events translated to actions and view state translated to domain state.

With these tools we believe you can write, if you want, an app that is type-safe from edge to edge.

helps to achieve modularity, componentization and code reuse between projects [tap to expand]

Middlewares should be focused in a very very small domain, performing only one type of work and reporting back in form of actions. Reducers should be focused in a very tiny combination of action and state. Views should have access to a really tiny portion of the state, or ideally to a view state that is a flat representation of the app global state using primitives that map directly to text field’s string, toggle’s boolean, progress bar’s double from 0.0 to 1.0 and so on and so forth.

Then, you can “lift” these three pieces - middleware, reducer, store projection - into the global state and action your app actually needs.

SwiftRex allows us to create small units-of-work that can be lifted to a global domain only when needed, so we can have Swift frameworks operating in a very specific domain, and covered with tests and Playgrounds/SwiftUI Previews to be used without having to launch the full app. Once this framework is ready, we just plug in our app, or even better, apps. Focusing on small domains will unlock better abstractions, and when this goes from middlewares (side-effect) to views, you have a powerful tool to define your building blocks.

enforces single source of truth and proper state management [tap to expand]

A trustable single source of truth that will never be inconsistent or out of sync among screens is possible with SwiftRex. It can be scary to think all your state is in a single place, a single tree that holds everything. It can be scary to see how much state you need, once you gather everything in a single place. But worry not, this is nothing that you didn’t have before, it was there already, in a ViewController, in a Presenter, in a flag used to control the result of a service, but because it was so spread you didn’t see how big it was. And worse, this leads to duplication, because when you need the same information from two different places, it’s easier to duplicate and hope that you’ll keep them in sync properly.

In fact, when you gather your whole app state in a unified tree, you start getting rid of lots of things you don’t need any more and your final state will be smaller than the messy one.

Writing the global state and the global action tree correctly can be challenging, but this is the app domain and reasoning about that is probably the most important task an engineer has to do.

For more information please check this link

offers tooling for development, tests and debugging [tap to expand]

Several projects offer SwiftRex tools to help developers when writing apps, tests, debugging it or evaluating crash reports.

CombineRextensions offers SwiftUI extensions to work with CombineRex, TestingExtensions has “test asserts” that will unlock testability of use cases in a fun and easy way, InstrumentationMiddleware allows you to use Instruments to see what’s happening in a SwiftRex app, SwiftRexMonitor will be a Swift version of well-known Redux DevTools where you can remotely monitor state and actions of an app from an external Mac or iOS device, and even inject actions to simulate side-effects (useful for UITests, for example), GatedMiddleware is a middleware wrapper that can be used to enable or disable other middlewares in runtime, LoggerMiddleware is a very powerful logger to be used by developers to easily understand what’s happening in runtime. More Middlewares will be open-sourced soon allowing, for example, to create good Crashlytics reports that tell the story of a crash as you’ve never had access before, and that way, recreate crashes or user reports. Also tools for generating code (Sourcery templates, Xcode snippets and templates, console tools), and also higher level APIs such as EffectMiddlewares that allow us to create Middlewares with a single function, as easy as Reducers are, or Handler that will allow to group Middlewares and Reducers under a same structure to be able to lift both together. New dependency injection strategies are about to be released as well.

All these tools are already done and will be released any time soon, and more are expected for the future.

I’m not gonna lie, it’s a completely different way of writing apps, as most reactive approaches are; but once you get used to, it makes more sense and enables you to reuse much more code between your projects, gives you better tooling for writing software, testing, debugging, logging and finally thinking about events, state and mutation as you’ve never done before. And I promise you, it’s gonna be a way with no return, an Unidirectional journey.

Reactive Framework Libraries

SwiftRex currently supports the 3 major reactive frameworks:

More can be easily added later by implementing some abstraction bridges that can be found in the ReactiveWrappers.swift file. To avoid adding unnecessary files to your app, SwiftRex is split in 4 packages:

- SwiftRex: the core library

- CombineRex: the implementation for Combine framework

- RxSwiftRex: the implementation for RxSwift framework

- ReactiveSwiftRex: the implementation for ReactiveSwift framework

SwiftRex itself won’t be enough, so you have to pick one of the three implementations.

Parts

Let’s understand the components of SwiftRex by splitting them into 3 sections:

Conceptual Parts

- State

Action

An Action represents an event that was notified by external (or sometimes internal) actors of your app. It’s about relevant INPUT events.

There’s no “Action” protocol or type in SwiftRex. However, Action will be found as a generic parameter for most core data structures, meaning that it’s up to you to define what is the root Action type.

Conceptually, we can say that an Action represents something that happens from external actors of your app, that means user interactions, timer callbacks, responses from web services, callbacks from CoreLocation and other frameworks. Some internal actors also can start actions, however. For example, when UIKit finishes loading your view we could say that viewDidLoad is an action, in case we’re interested in this event. Same for SwiftUI View (.onAppear, .onDisappear, .onTap) or Gesture (.onEnded, .onChanged, .updating) modifiers, they all can be considered actions. When URLSession replies with a Data that we were able to parse into a struct, this can be a successful action, but when the response is a 404, or JSONDecoder can’t understand the payload, this should also become a failure Action. NotificationCenter does nothing else but notifying actions from all over the system, such as keyboard dismissal or device rotation. CoreData and other realtime databases have mechanism to notify when something changed, and this should become an action as well.

Actions are about INPUT events that are relevant for an app.

For representing an action in your app you can use structs, classes or enums, and organize the list of possible actions the way you think it’s better. But we have a recommended way that will enable you to fully use type-safety and avoid problems, and this way is by using a tree structure created with enums and associated values.

enum AppAction {

case started

case movie(MovieAction)

case cast(CastAction)

}

enum MovieAction {

case requestMovieList

case gotMovieList(movies: [Movie])

case movieListResponseError(MovieResponseError)

case selectMovie(id: UUID)

}

enum CastAction {

case requestCastList(movieId: UUID)

case gotCastList(movieId: UUID, cast: [Person])

case castListResponseError(CastResponseError)

case selectPerson(id: UUID)

}

All possible events in your app should be listed in these enums and grouped the way you consider more relevant. When grouping these enums one thing to consider is modularity: you can split some or all these enums in different frameworks if you want strict boundaries between your modules and/or reuse the same group of actions among different apps.

For example, all apps will have common actions that represent life-cycle of any iOS app, such as willResignActive, didBecomeActive, didEnterBackground, willEnterForeground. If multiples apps need to know this life-cycle, maybe it’s convenient to create an enum for this specific domain. The same for network reachability, we should consider creating an enum to represent all possible events we get from the system when our connection state changes, and this can be used in a wide variety of apps.

IMPORTANT: Because enums in Swift don’t have KeyPath as structs do, we strongly recommend reading Action Enum Properties document and implementing properties for each case, either manually or using code generators, so later you avoid writing lots and lots of error-prone switch/case. We also offer some templates to help you on that.

State

State represents the whole knowledge that an app holds while is open, usually in memory and mutable. It’s about relevant OUTPUT properties.

There’s no “State” protocol or type in SwiftRex. However, State will be found as a generic parameter for most core data structures, meaning that it’s up to you to define what is the root State type.

Conceptually, we can say that state represents the whole knowledge that an app holds while is open, usually in memory and mutable; it’s like a paper on where you write down some values, and for every action you receive you erase one value and replace it by a different value. Another way of thinking about state is in a functional programming way: the state is not persisted, but it’s the result of a function that takes the initial condition of your app plus all the actions it received since it was launched, and calculates the current values by applying chronologically all the action changes on top of the initial state. This is known as Event Sourcing Design Pattern and it’s becoming popular recently in some web backend services, such as Kafka Event Sourcing.

In a device with limited battery and memory we can’t afford having a true event-sourcing pattern because it would be too expensive recreating the whole history of an app every time someone requests a simple boolean. So we “cache” the new state every time an action is received, and this in-memory cache is precisely what we call “State” in SwiftRex. So maybe we mix both ways of thinking about State and come up with a better generalisation for what a state is.

STATE is the result of a function that takes two arguments: the previous (or initial) state and some action that occurred, to determine the new state. This happens incrementally as more and more actions arrive. State is useful for output data to the user.

However, be careful, some things may look like state but they are not. Let’s assume you have an app that shows an item price to the user. This price will be shown as "$3.00" in US, or "$3,00" in Germany, or maybe this product can be listed in british pounds, so in US we should show "£3.00" while in Germany it would be "£3,00". In this example we have:

- Currency type (

£or$) - Numeric value (

3) - Locale (

en_USorde_DE) - Formatted string (

"$3.00","$3,00","£3.00"or"£3,00")

The formatted string itself is NOT state, because it can be calculated from the other properties. This can be called “derived state” and holding that is asking for inconsistency. We would have to remember to update this value every time one of the others change. So it’s better off to represent this String either as a calculated property or a function of the other 3 values. The best place for this sort of derived state is in presenters or controllers, unless you have a high cost to recalculate it and in this case you could store in the state and be very careful about it. Luckily SwiftRex helps to keep the state consistent as we’re about to see in the Reducer section, still, it’s better off not duplicating information that can be easily and cheaply calculated.

For representing the state of an app we recommend value types: structs or enums. Tuples would be acceptable as well, but unfortunately Swift currently doesn’t allow us to conform tuples to protocols, and we usually want our whole state to be Equatable and sometimes Codable.

struct AppState: Equatable {

var appLifecycle: AppLifecycle

var movies: Loadable<[Movie]> = .neverLoaded

var currentFilter: MovieFilter

var selectedMovie: UUID?

}

struct MovieFilter: Equatable {

var stringFilter: String?

var yearMin: Int?

var yearMax: Int?

var ratingMin: Int?

var ratingMax: Int?

}

enum AppLifecycle: Equatable {

case backgroundActive

case backgroundInactive

case foregroundActive

case foregroundInactive

}

enum Loadable<T> {

case neverLoaded

case loading

case loaded(T)

}

extension Loadable: Equatable where T: Equatable {}

Some properties represent a state-machine, for example the Loadable enum will eventually change from .neverLoaded to .loading and then to .loaded([Movie]) in our movies property. Learning when and how to represent properties in this shape is a matter of experimenting more and more with SwiftRex and getting used to this architecture. Eventually this will become natural and you can start writing your own data structures to represent such state-machines, that will be very useful in countless situations.

Annotating the whole state as Equatable helps us to reduce the UI updates in case view models are not used, but this is not a strong requirement and there are other ways to also avoid that, although we still recommend it. Annotating the state as Codable can be useful for logging, debugging, crash reports, monitors, etc and this is also recommended if possible.

Core Parts

Store

StoreType

A protocol that defines the two expected roles of a “Store”: receive/distribute actions (ActionHandler); and publish changes of the the current app state (StateProvider) to possible subscribers. It can be a real store (such as ReduxStoreBase) or just a “proxy” that acts on behalf of a real store, for example, in the case of StoreProjection.

Store Type is an ActionHandler, which means actors can dispatch actions (ActionHandler/dispatch(_:)) that will be handled by this store. These actions will eventually start side-effects or change state. These actions can also be dispatched by the result of side-effects, like the callback of an API call, or CLLocation new coordinates. How this action is handled will depend on the different implementations of StoreType.

Store Type is also a StateProvider, which means it’s aware of certain state and can notify possible subscribers about changes through its publisher (StateProvider/statePublisher). If this StoreType owns the state (single source-of-truth) or only proxies it from another store will depend on the different implementations of the protocol.

┌──────────┐

│ UIButton │────────┐

└──────────┘ │

┌───────────────────┐ │ dispatch<Action>(_ action: Action)

│UIGestureRecognizer│───┼──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

└───────────────────┘ │ │

┌───────────┐ │ ▼

│viewDidLoad│───────┘ ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓

└───────────┘ ┃ ┃░

┃ ┃░

┃ ┃░

┌───────┐ ┃ ┃░

│UILabel│◀─ ─ ─ ─ ┐ ┃ ┃░

└───────┘ Combine, RxSwift ┌ ─ ─ ┻ ─ ┐ ┃░

│ or ReactiveSwift State Store ┃░

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─│Publisher│ ┃░

▼ │ subscribe(onNext:) ┃░

┌─────────────┐ ▼ sink(receiveValue:) └ ─ ─ ┳ ─ ┘ ┃░

│ Diffable │ ┌─────────────┐ assign(to:on:) ┃ ┃░

│ DataSource │ │RxDataSources│ ┃ ┃░

└─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ ┃ ┃░

│ │ ┃ ┃░

┌──────▼───────────────▼───────────┐ ┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┛░

│ │ ░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░

│ │

│ │

│ │

│ UICollectionView │

│ │

│ │

│ │

│ │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

There are implementations that will be the actual Store, the one and only instance that will be the central hub for the whole redux architecture. Other implementations can be only projections or the main Store, so they act like a Store by implementing the same roles, but instead of owning the global state or handling the actions directly, these projections only apply some small (and pure) transformation in the chain and delegate to the real Store. This is useful when you want to have local “stores” in your views, but you don’t want them to duplicate data or own any kind of state, but only act as a store while using the central one behind the scenes.

For more information about real stores, please check ReduxStoreBase and ReduxStoreProtocol, and for more information about the projections

please check StoreProjection and StoreType/projection(action:state:).

Real Store?

A real Store is a class that you want to create and keep alive during the whole execution of an app, because its only responsibility is to act as a

coordinator for the Unidirectional Dataflow lifecycle. That’s also why we want one and only one instance of a Store, so either you create a static

instance singleton, or keep it in your AppDelegate. Be careful with SceneDelegate if your app supports multiple windows and you want to share the

state between these multiple instances of your app, which you usually want. That’s why AppDelegate, singleton or global variable is usually

recommended for the Store, not SceneDelegate. In case of SwiftUI you can create a store in your app protocol as a Combine/StateObject:

@main

struct MyApp: App {

@StateObject var store = Store.createStore(dependencyInjection: World.default).asObservableViewModel(initialState: .initial)

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

ContentView(viewModel: ContentViewModel(store: store))

}

}

}

SwiftRex will provide a protocol (ReduxStoreProtocol) and a base class (ReduxStoreBase) for helping you to create your own Store.

class Store: ReduxStoreBase<AppAction, AppState> {

static func createStore(dependencyInjection: World) -> Store {

let store = Store(

subject: .combine(initialValue: .initial),

reducer: AppModule.appReducer,

middleware: AppModule.appMiddleware(dependencyInjection: dependencyInjection)

emitsValue: .whenDifferent

)

store.dispatch(AppAction.lifecycle(LifeCycleAction.start))

return store

}

}

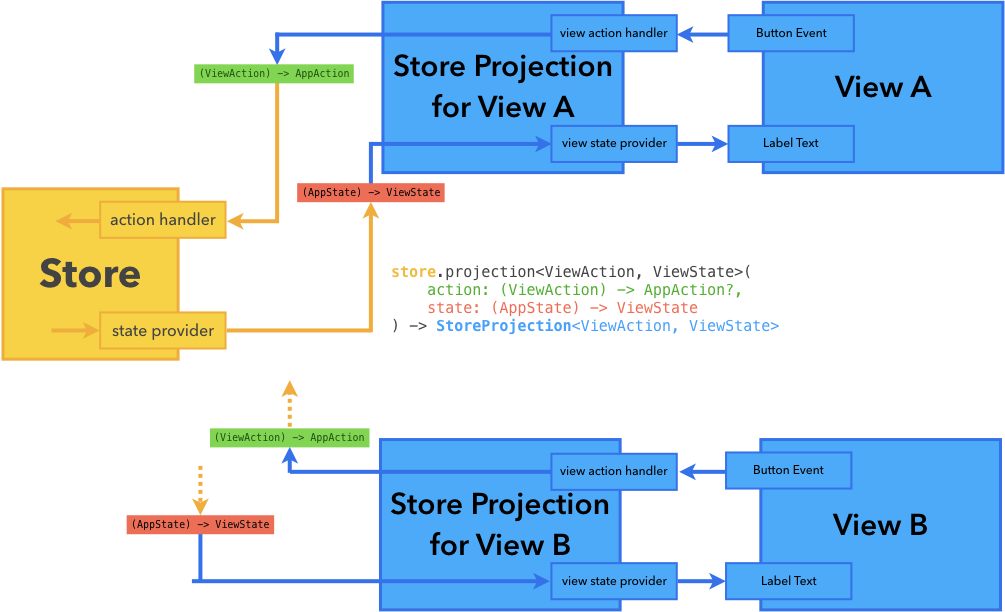

What is a Store Projection?

Very often you don’t want your view to be able to access the whole App State or dispatch any possible global App Action. Not only it could refresh your UI more often than needed, it also makes more error prone, put more complex code in the view layer and finally decreases modularisation making the view coupled to the global models.

However, you don’t want to split your state in multiple parts because having it in a central and unique point ensures consistency. Also, you don’t want multiple separate places taking care of actions because that could potentially create race conditions. The real Store is the only place actually owning the global state and effectively handling the actions, and that’s how it’s supposed to be.

To solve both problems, we offer a StoreProjection, which conforms to the StoreType protocol so for all purposes it behaves like a real store,

but in fact it only projects the real store using custom types for state and actions, that is, either a subset of your models (a branch in the state

tree, for example), or a completely different entity like a View State. A StoreProjection has 2 closures, that allow it to transform actions and

state between the global ones and the ones used by the view. That way, the View is not coupled to the whole global models, but only to tiny parts of

it, and the closure in the StoreProjection will take care of extracting/mapping the interesting part for the view. This also improves performance,

because the view will not refresh for any property in the global state, only for the relevant ones. On the other direction, view can only dispatch a

limited set of actions, that will be mapped into global actions by the closure in the StoreProjection.

A Store Projection can be created from any other StoreType, even from another StoreProjection. It’s as simple as calling

StoreType/projection(action:state:), and providing the action and state mapping closures:

let storeProjection = store.projection(

action: { viewAction in viewAction.toAppAction() } ,

state: { globalState in MyViewState.from(globalState: globalState) }

).asObservableViewModel(initialState: .empty)

All together

Putting everything together we could have:

@main

struct MyApp: App {

@StateObject var store = Store.createStore(dependencyInjection: World.default).asObservableViewModel(initialState: .initial)

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

ContentView(

viewModel: store.projection(

action: { (viewAction: ContentViewAction) -> AppAction? in

viewAction.toAppAction()

},

state: { (globalState: AppState) -> ContentViewState in

ContentViewState.from(globalState: globalState)

}

).asObservableViewModel(initialState: .empty)

)

}

}

}

struct ContentViewState: Equatable {

let title: String

static func from(globalState: AppState) -> ContentViewState {

ContentViewState(title: "\(L10n.goodMorning), \(globalState.foo.bar.title)")

}

}

enum ContentViewAction {

case onAppear

func toAppAction() -> AppAction? {

switch self {

case .onAppear: return AppAction.foo(.bar(.startTimer))

}

}

}

In this example above we can see that ContentView doesn’t know about the global models, it’s limited to ContentViewAction and ContentViewState

only. It also only refreshes when globalState.foo.bar.title changes, any other change in the AppState will be ignored because the other properties

are not mapped into anything in the ContentViewState. Also, ContentViewAction has a single case, onAppear, and that’s the only thing the view

can dispatch, without knowing that this will eventually start a timer (AppAction.foo(.bar(.startTimer))). The view should not know about domain

logic and its actions should be limited to buttonTapped, onAppear, didScroll, toggle(enabled: Bool) and other names that only suggest UI

interaction. How this is mapped into App Actions is responsibility of other parts, in our example, ContentViewAction itself, but it could be a

Presenter layer, a View Model layer, or whatever structure you decide to create to organise your code.

Testing is also made easier with this approach, as the View doesn’t hold any logic and the projection transformations are pure functions.

Middleware

MiddlewareProtocol is a plugin, or a composition of several plugins, that are assigned to the app global StoreType pipeline in order to handle each action received (InputActionType), to execute side-effects in response, and eventually dispatch more actions (OutputActionType) in the process. It can also access the most up-to-date StateType while handling an incoming action.

We can think of a Middleware as an object that transforms actions into sync or async tasks and create more actions as these side-effects complete, also being able to check the current state while handling an action.

An Action is a lightweight structure, typically an enum, that is dispatched into the ActionHandler (usually a StoreType).

A Store like ReduxStoreProtocol enqueues a new action that arrives and submits it to a pipeline of middlewares. So, in other words, a MiddlewareProtocol is class that handles actions, and has the power to dispatch more actions, either immediately or after callback of async tasks. The middleware can also simply ignore the action, or it can execute side-effects in response, such as logging into file or over the network, or execute http requests, for example. In case of those async tasks, when they complete the middleware can dispatch new actions containing a payload with the response (a JSON file, an array of movies, credentials, etc). Other middlewares will handle that, or maybe even the same middleware in the future, or perhaps some Reducer will use this action to change the state, because the MiddlewareProtocol itself can never change the state, only read it.

The MiddlewareProtocol/handle(action:from:state:) will be called before the Reducer, so if you read the state at that point it’s still going to be the unchanged version. While implementing this function, it’s expected that you return an IO object, which is basically a closure where you can perform side-effects and dispatch new actions. Inside this closure, the state will have the new values after the reducers handled the current action, so in case you made a copy of the old state, you can compare them, log, audit, perform analytics tracking, telemetry or state sync with external devices, such as Apple Watches. Remote Debugging over the network is also a great use of a Middleware.

Every action dispatched also comes with its action source, which is the primary dispatcher of that action. Middlewares can access the file name, line of code, function name and additional information about the entity responsible for creating and dispatching that action, which is a very powerful debugging information that can help developers to trace how the information flows through the app.

Ideally a MiddlewareProtocol should be a small and reusable box, handling only a very limited set of actions, and combined with other small middlewares to create more complex apps. For example, the same CoreLocation middleware could be used from an iOS app, its extensions, the Apple Watch extension or even different apps, as long as they share some sub-action tree and sub-state struct.

Some suggestions of middlewares:

- Run Timers, pooling some external resource or updating some local state at a constant time

- Subscribe for

CoreData,Realm,Firebase Realtime Databaseor equivalent database changes - Be a

CoreLocationdelegate, checking for significant location changes or beacon ranges and triggering actions to update the state - Be a

HealthKitdelegate to track activities, or even combining that withCoreLocationobservation in order to track the activity route - Logger, Telemetry, Auditing, Analytics tracker, Crash report breadcrumbs

- Monitoring or debugging tools, like external apps to monitor the state and actions remotely from a different device

WatchConnectivitysync, keep iOS and watchOS state in sync- API calls and other “cold observables”

- Network Reachability

- Navigation through the app (Redux Coordinator pattern)

CoreBluetoothcentral or peripheral managerCoreNFCmanager and delegateNotificationCenterand other delegates- WebSocket, TCP Socket, Multipeer and many other connectivity protocols

RxSwiftobservables,ReactiveSwiftsignal producers,Combinepublishers- Observation of traits changes, device rotation, language/locale, dark mode, dynamic fonts, background/foreground state

- Any side-effect, I/O, networking, sensors, third-party libraries that you want to abstract

┌────────┐

IO closure ┌─▶│ View 1 │

┌─────┐ (don't run yet) ┌─────┐ │ └────────┘

│ │ handle ┌──────────┐ ┌───────────────────────────────────────▶│ │ send │ ┌────────┐

│ ├────────▶│Middleware│──┘ │ │────────────▶├─▶│ View 2 │

│ │ Action │ Pipeline │──┐ ┌─────┐ reduce ┌──────────┐ │ │ New state │ └────────┘

│ │ └──────────┘ └─▶│ │───────▶│ Reducer │──────────▶│ │ │ ┌────────┐

┌──────┐ dispatch │ │ │Store│ Action │ Pipeline │ New state │ │ └─▶│ View 3 │

│Button│─────────▶│Store│ │ │ + └──────────┘ │Store│ └────────┘

└──────┘ Action │ │ └─────┘ State │ │ dispatch ┌─────┐

│ │ │ │ ┌─────────────────────────┐ New Action │ │

│ │ │ │─run──▶│ IO closure ├────────────▶│Store│─ ─ ▶ ...

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ └─┬───────────────────────┘ └─────┘

└─────┘ └─────┘ │ ▲

request│ side-effects │side-effects

▼ response

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ │

External │─ ─ async ─ ─ ─

│ World

─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘

Generics

Middleware protocol is generic over 3 associated types:

InputActionType:The Action type that this

MiddlewareProtocolknows how to handle, so the store will forward actions of this type to this middleware.Most of the times middlewares don’t need to handle all possible actions from the whole global action tree, so we can decide to allow it to focus only on a subset of the action.

In this case, this action type can be a subset to be lifted to a global action type in order to compose with other middlewares acting on the global action of an app. Please check Lifting for more details.

OutputActionType:The Action type that this

MiddlewareProtocolwill eventually trigger back to the store in response of side-effects. This can be the same asInputActionTypeor different, in case you want to separate your enum in requests and responses.Most of the times middlewares don’t need to dispatch all possible actions of the whole global action tree, so we can decide to allow it to dispatch only a subset of the action, or not dispatch any action at all, so the

OutputActionTypecan safely be set toNever.In this case, this action type can be a subset to be lifted to a global action type in order to compose with other middlewares acting on the global action of an app. Please check Lifting for more details.

StateType:The State part that this

MiddlewareProtocolneeds to read in order to make decisions. This middleware will be able to read the most up-to-dateStateTypefrom the store while handling an incoming action, but it can never write or make changes to it.Most of the times middlewares don’t need reading the whole global state, so we can decide to allow it to read only a subset of the state, or maybe this middleware doesn’t need to read any state, so the

StateTypecan safely be set toVoid.In this case, this state type can be a subset to be lifted to a global state in order to compose with other middlewares acting on the global state of an app. Please check Lifting for more details.

Returning IO and performing side-effects

In its most important function, MiddlewareProtocol/handle(action:from:state:) the middleware is expected to return an IO object, which is a closure where side-effects should be executed and new actions can be dispatched.

In some cases, we may want to not execute any side-effect or run any code after reducer, in that case, the function can return a simple IO/pure().

Otherwise, return the closure that takes the output (of ActionHandler type, that accepts ActionHandler/dispatch(_:) calls):

public func handle(action: InputActionType, from dispatcher: ActionSource, state: @escaping GetState<StateType>) -> IO<OutputActionType> {

if action != .myExpectedAction { return .pure() }

return IO { output in

output.dispatch(.showPopup)

DispatchQueue.global().asyncAfter(.now() + .seconds(3)) {

output.dispatch(.hidePopup)

}

}

}

Dependency Injection

Testability is one of the most important aspects to account for when developing software. In Redux architecture, MiddlewareProtocol is the only type of object allowed to perform side-effects, so it’s the only place where the testability can be challenging.

To improve testability, the middleware should use as few external dependencies as possible. If it starts to use too many, consider splitting in smaller middlewares, this will also protect you against race conditions and other problems, will help with tests and make the middleware more reusable.

Also, all external dependencies should be injected in the initialiser, so during the tests you can replace them with mocks. If your middleware uses only one call from a very complex object, instead of using a protocol full of functions please consider either creating a protocol with a single function requirement, or even inject a closure such as @escaping (URLRequest) -> AnyPublisher<(Data, URLResponse), Error>. Creating mocks for this will be way much easier.

Finally, consider using MiddlewareReader to wrap this middleware in a dependency injection container.

Middleware Examples

When implementing your Middleware, all you have to do is to handle the incoming actions:

public final class LoggerMiddleware: MiddlewareProtocol {

public typealias InputActionType = AppGlobalAction // It wants to receive all possible app actions

public typealias OutputActionType = Never // No action is generated from this Middleware

public typealias StateType = AppGlobalState // It wants to read the whole app state

private let logger: Logger

private let now: () -> Date

// Dependency Injection

public init(logger: Logger = Logger.default, now: @escaping () -> Date) {

self.logger = logger

self.now = now

}

// inputAction: AppGlobalAction state: AppGlobalState output action: Never

public func handle(action: InputActionType, from dispatcher: ActionSource, state: @escaping GetState<StateType>) -> IO<OutputActionType> {

let stateBefore: AppGlobalState = state()

let dateBefore = now()

return IO { [weak self] output in

guard let self = self else { return }

let stateAfter = state()

let dateAfter = self.now()

let source = "\(dispatcher.file):\(dispatcher.line) - \(dispatcher.function) | \(dispatcher.info ?? "")"

self.logger.log(action: action, from: source, before: stateBefore, after: stateAfter, dateBefore: dateBefore, dateAfter: dateAfter)

}

}

}

public final class FavoritesAPIMiddleware: MiddlewareProtocol {

public typealias InputActionType = FavoritesAction // It wants to receive only actions related to Favorites

public typealias OutputActionType = FavoritesAction // It wants to also dispatch actions related to Favorites

public typealias StateType = FavoritesModel // It wants to read the app state that manages favorites

private let api: API

// Dependency Injection

public init(api: API) {

self.api = api

}

// inputAction: FavoritesAction state: FavoritesModel output action: FavoritesAction

public func handle(action: InputActionType, from dispatcher: ActionSource, state: @escaping GetState<StateType>) -> IO<OutputActionType> {

guard case let .toggleFavorite(movieId) = action else { return .pure() }

let favoritesList = state() // state before reducer

let makeFavorite = !favoritesList.contains(where: { $0.id == movieId })

return IO { [weak self] output in

guard let self = self else { return }

self.api.changeFavorite(id: movieId, makeFavorite: makeFavorite) (completion: { result in

switch result {

case let .success(value):

output.dispatch(.changedFavorite(movieId, isFavorite: makeFavorite), info: "API.changeFavorite callback")

case let .failure(error):

output.dispatch(.changedFavoriteHasFailed(movieId, isFavorite: !makeFavorite, error: error), info: "api.changeFavorite callback")

}

})

}

}

}

EffectMiddleware

This is a middleware implementation that aims for simplicity while keeping it very powerful. For every incoming action you must return an Effect, which is simply a wrapper for a reactive

Observable, Publisher or SignalProducer, depending on your favourite reactive library. The only condition is that the Output (Element) of your reactive stream must be a DispatchedAction and

the Error must be Never. DispatchedAction is a struct having the action itself and the dispatcher (action source), so it’s generic over the Action and matches the OutputAction of the

EffectMiddleware. Error must be Never because Middlewares are expected to resolve all side-effects, including Errors. So if you want to treat the error, you can do it in the middleware, if

you want to warn the user about the error, then you catch the error in your reactive stream and transform it into an Action such as .somethingWentWrong(messageToTheUser: String) to be

dispatched and later reduced into the AppState.

Optionally an EffectMiddleware can also handle Dependencies. This helps to perform Dependency Injection into the middleware. If your Dependency generic parameter is Void, then the Middleware can be created immediately without passing any dependency, however you can’t use any external dependency when handling the action. If Dependency generic parameter has some type, or tuple, then you can use them while handling the action, but in order to create the effect middleware you will need to provide that type or tuple.

Important: the dependency will be available inside the Effect closure only, because it’s expected that you “access” the external world only while executing an Effect.

static let favouritesMiddleware = EffectMiddleware<FavoritesAction /* input action */, FavoritesAction /* output action */, AppState, FavouritesAPI /* dependencies */>.onAction { incomingAction, dispatcher, getState in

switch incomingAction {

case let .toggleFavorite(movieId):

return Effect(token: "Any Hashable. Use this to cancel tasks, or to avoid two tasks of the same type") { context -> AnyPublisher<DispatchedAction<FavoritesAction>, Never> in

let favoritesList = getState()

let makeFavorite = !favoritesList.contains(where: { $0.id == movieId })

let api = context.dependencies

return api.changeFavoritePublisher(id: movieId, makeFavorite: makeFavorite)

.catch { error in DispatchedAction(.somethingWentWrong("Got an error: \(error)") }

.eraseToAnyPublisher()

}

default:

return .doNothing // Special type of Effect that, well, does nothing.

}

}

Effect has some useful constructors such as .doNothing, .fireAndForget, .just, .sequence, .promise, .toCancel and others. Also, you can lift any Publisher, Observable or SignalProducer into an Effect, as

long as it matches the required generic parameters, for that you can simply use .asEffect() functions.

Reducer

Reducer is a pure function wrapped in a monoid container, that takes an action and the current state to calculate the new state.

The MiddlewareProtocol pipeline can do two things: dispatch outgoing actions and handling incoming actions. But what they can NOT do is changing the app state. Middlewares have read-only access to the up-to-date state of our apps, but when mutations are required we use the MutableReduceFunction function:

(ActionType, inout StateType) -> Void

Which has the same semantics (but better performance) than old ReduceFunction:

(ActionType, StateType) -> StateType

Given an action and the current state (as a mutable inout), it calculates the new state and changes it:

initial state is 42

action: increment

reducer: increment 42 => new state 43

current state is 43

action: decrement

reducer: decrement 43 => new state 42

current state is 42

action: half

reducer: half 42 => new state 21

The function is reducing all the actions in a cached state, and that happens incrementally for each new incoming action.

It’s important to understand that reducer is a synchronous operations that calculates a new state without any kind of side-effect (including non-obvious ones as creating Date(), using DispatchQueue or Locale.current), so never add properties to the Reducer structs or call any external function. If you are tempted to do that, please create a middleware and dispatch actions with Dates or Locales from it.

Reducers are also responsible for keeping the consistency of a state, so it’s always good to do a final sanity check before changing the state, like for example check other dependant properties that must be changed together.

Once the reducer function executes, the store will update its single source-of-truth with the new calculated state, and propagate it to all its subscribers, that will react to the new state and update Views, for example.

This function is wrapped in a struct to overcome some Swift limitations, for example, allowing us to compose multiple reducers into one (monoid operation, where two or more reducers become a single one) or lifting reducers from local types to global types.

The ability to lift reducers allow us to write fine-grained “sub-reducer” that will handle only a subset of the state and/or action, place it in different frameworks and modules, and later plugged into a bigger state and action handler by providing a way to map state and actions between the global and local ones. For more information about that, please check Lifting.

A possible implementation of a reducer would be:

let volumeReducer = Reducer<VolumeAction, VolumeState>.reduce { action, currentState in

switch action {

case .louder:

currentState = VolumeState(

isMute: false, // When increasing the volume, always unmute it.

volume: min(100, currentState.volume + 5)

)

case .quieter:

currentState = VolumeState(

isMute: currentState.isMute,

volume: max(0, currentState.volume - 5)

)

case .toggleMute:

currentState = VolumeState(

isMute: !currentState.isMute,

volume: currentState.volume

)

}

}

Please notice from the example above the following good practices:

- No

DispatchQueue, threading, operation queue, promises, reactive code in there. - All you need to implement this function is provided by the arguments

actionandcurrentState, don’t use any other variable coming from global scope, not even for reading purposes. If you need something else, it should either be in the state or come in the action payload. - Do not start side-effects, requests, I/O, database calls.

- Avoid

defaultwhen writingswitch/casestatements. That way the compiler will help you more. - Make the action and the state generic parameters as much specialised as you can. If volume state is part of a bigger state, you should not be tempted to pass the whole big state into this reducer. Make it short, brief and specialised, this also helps preventing

defaultcase or having to re-assign properties that are never mutated by this reducer.

┌────────┐

IO closure ┌─▶│ View 1 │

┌─────┐ (don't run yet) ┌─────┐ │ └────────┘

│ │ handle ┌──────────┐ ┌───────────────────────────────────────▶│ │ send │ ┌────────┐

│ ├────────▶│Middleware│──┘ │ │────────────▶├─▶│ View 2 │

│ │ Action │ Pipeline │──┐ ┌─────┐ reduce ┌──────────┐ │ │ New state │ └────────┘

│ │ └──────────┘ └─▶│ │───────▶│ Reducer │──────────▶│ │ │ ┌────────┐

┌──────┐ dispatch │ │ │Store│ Action │ Pipeline │ New state │ │ └─▶│ View 3 │

│Button│─────────▶│Store│ │ │ + └──────────┘ │Store│ └────────┘

└──────┘ Action │ │ └─────┘ State │ │ dispatch ┌─────┐

│ │ │ │ ┌─────────────────────────┐ New Action │ │

│ │ │ │─run──▶│ IO closure ├────────────▶│Store│─ ─ ▶ ...

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ └─┬───────────────────────┘ └─────┘

└─────┘ └─────┘ │ ▲

request│ side-effects │side-effects

▼ response

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ │

External │─ ─ async ─ ─ ─

│ World

─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘

Projection and Lifting

Store Projection

An app should have a single real Store, holding a single source-of-truth. However, we can “derive” this store to small subsets, called store projections, that will handle either a smaller part of the state or action tree, or even a completely different type of actions and states as long as we can map back-and-forth to the original store types. It won’t store anything, only project the original store. For example, a View can define a completely custom View State and View Action, and we can create a StoreProjection that works on these types, as long as it’s backed by a real store which State and Action types can be mapped somehow to the View State and View Action types. The Store Projection will take care of translating these entities.

Very often you don’t want your view to be able to access the whole App State or dispatch any possible global App Action. Not only it could refresh your UI more often than needed, it also makes more error prone, put more complex code in the view layer and finally decreases modularisation making the view coupled to the global models.

However, you don’t want to split your state in multiple parts because having it in a central and unique point ensures consistency. Also, you don’t want multiple separate places taking care of actions because that could potentially create race conditions. The real Store is the only place actually owning the global state and effectively handling the actions, and that’s how it’s supposed to be.

To solve both problems, we offer a StoreProjection, which conforms to the StoreType protocol so for all purposes it behaves like a real store,

but in fact it only projects the real store using custom types for state and actions, that is, either a subset of your models (a branch in the state

tree, for example), or a completely different entity like a View State. A StoreProjection has 2 closures, that allow it to transform actions and

state between the global ones and the ones used by the view. That way, the View is not coupled to the whole global models, but only to tiny parts of

it, and the closure in the StoreProjection will take care of extracting/mapping the interesting part for the view. This also improves performance,

because the view will not refresh for any property in the global state, only for the relevant ones. On the other direction, view can only dispatch a

limited set of actions, that will be mapped into global actions by the closure in the StoreProjection.

A Store Projection can be created from any other StoreType, even from another StoreProjection. It’s as simple as calling

StoreType/projection(action:state:), and providing the action and state mapping closures:

let storeProjection = store.projection(

action: { viewAction in viewAction.toAppAction() } ,

state: { globalState in MyViewState.from(globalState: globalState) }

).asObservableViewModel(initialState: .empty)

For more information about real store vs. store projections, and also for complete code examples, please check documentation for StoreType.

Lifting

An app can be a complex product, performing several activities that not necessarily are related. For example, the same app may need to perform a request to a weather API, check the current user location using CLLocation and read preferences from UserDefaults.

Although these activities are combined to create the full experience, they can be isolated from each other in order to avoid URLSession logic and CLLocation logic in the same place, competing for the same resources and potentially causing race conditions. Also, testing these parts in isolation is often easier and leads to more significant tests.

Ideally we should organise our AppState and AppAction to account for these parts as isolated trees. In the example above, we could have 3 different properties in our AppState and 3 different enum cases in our AppAction to group state and actions related to the weather API, to the user location and to the UserDefaults access.

This gets even more helpful in case we split our app in 3 types of Reducer and 3 types of MiddlewareProtocol, and each of them work not on the full AppState and AppAction, but in the 3 paths we grouped in our model. The first pair of Reducer and MiddlewareProtocol would be generic over WeatherState and WeatherAction, the second pair over LocationState and LocationAction and the third pair over RepositoryState and RepositoryAction. They could even be in different frameworks, so the compiler will forbid us from coupling Weather API code with CLLocation code, which is great as this enforces better practices and unlocks code reusability. Maybe our CLLocation middleware/reducer can be useful in a completely different app that checks for public transport routes.

But at some point we want to put these 3 different types of entities together, and the StoreType of our app “speaks” AppAction and AppState, not the subsets used by the specialised handlers.

enum AppAction {

case weather(WeatherAction)

case location(LocationAction)

case repository(RepositoryAction)

}

struct AppState {

let weather: WeatherState

let location: LocationState

let repository: RepositoryState

}

Given a reducer that is generic over WeatherAction and WeatherState, we can “lift” it to the global types AppAction and AppState by telling this reducer how to find in the global tree the properties that it needs. That would be \AppAction.weather and \AppState.weather. The same can be done for the middleware, and for the other 2 reducers and middlewares of our app.

When all of them are lifted to a common type, they can be combined together using the diamond operator (<>) and set as the store handler.

IMPORTANT: Because enums in Swift don’t have KeyPath as structs do, we strongly recommend reading Action Enum Properties document and implementing properties for each case, either manually or using code generators, so later you avoid writing lots and lots of error-prone switch/case. We also offer some templates to help you on that.

Let’s explore how to lift reducers and middlewares.

Lifting Reducer

Reducer has AppAction INPUT, AppState INPUT and AppState OUTPUT, because it can only handle actions (never dispatch them), read the state and write the state.

The lifting direction, therefore, should be:

Reducer:

- ReducerAction? ← AppAction

- ReducerState ←→ AppState

Given:

// type 1 type 2

Reducer<ReducerAction, ReducerState>

Transformations:

╔═══════════════════╗

║ ║

╔═══════════════╗ ║ ║

║ Reducer ║ .lift ║ Store ║

╚═══════════════╝ ║ ║

│ ║ ║

╚═══════════════════╝

│ │

│ │

┌───────────┐

┌─────┴─────┐ (AppAction) -> ReducerAction? │ │

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┐ │ Reducer │ { $0.case?.reducerAction } │ │

Input Action │ Action │◀──────────────────────────────────────────────│ AppAction │

└ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘ │ │ KeyPath<AppAction, ReducerAction?> │ │

└─────┬─────┘ \AppAction.case?.reducerAction │ │

└───────────┘

│ │

│ get: (AppState) -> ReducerState │

{ $0.reducerState } ┌───────────┐

┌─────┴─────┐ set: (inout AppState, ReducerState) -> Void │ │

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┐ │ Reducer │ { $0.reducerState = $1 } │ │

State │ State │◀─────────────────────────────────────────────▶│ AppState │

└ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘ │ │ WritableKeyPath<AppState, ReducerState> │ │

└─────┬─────┘ \AppState.reducerState │ │

└───────────┘

│ │

Lifting Reducer using closures:

.lift(

actionGetter: { (action: AppAction) -> ReducerAction? /* type 1 */ in

// prism3 has associated value of ReducerAction,

// and whole thing is Optional because Prism is always optional

action.prism1?.prism2?.prism3

},

stateGetter: { (state: AppState) -> ReducerState /* type 2 */ in

// property2: ReducerState

state.property1.property2

},

stateSetter: { (state: inout AppState, newValue: ReducerState /* type 2 */) -> Void in

// property2: ReducerState

state.property1.property2 = newValue

}

)

Steps:

- Start plugging the 2 types from the Reducer into the 3 closure headers.

- For type 1, find a prism that resolves from AppAction into the matching type. BE SURE TO RUN SOURCERY AND HAVING ALL ENUM CASES COVERED BY PRISM

- For type 2 on the stateGetter closure, find lenses (property getters) that resolve from AppState into the matching type.

- For type 2 on the stateSetter closure, find lenses (property setters) that can change the global state receive to the newValue received. Be sure that everything is writeable.

Lifting Reducer using KeyPath:

.lift(

action: \AppAction.prism1?.prism2?.prism3,

state: \AppState.property1.property2

)

Steps:

- Start with the closure example above

- For action, we can use KeyPath from

\AppActiontraversing the prism tree - For state, we can use WritableKeyPath from

\AppStatetraversing the properties as long as all of them are declared asvar, notlet.

Lifting Middleware

MiddlewareProtocol has AppAction INPUT, AppAction OUTPUT and AppState INPUT, because it can handle actions, dispatch actions, and only read the state (never write it).

The lifting direction, therefore, should be:

Middleware:

- MiddlewareInputAction? ← AppAction

- MiddlewareOutputAction → AppAction

- MiddlewareState ← AppState

Given:

// type 1 type 2 type 3

MyMiddleware<MiddlewareInputAction, MiddlewareOutputAction, MiddlewareState>

Transformations:

╔═══════════════════╗

║ ║

╔═══════════════╗ ║ ║

║ Middleware ║ .lift ║ Store ║

╚═══════════════╝ ║ ║

│ ║ ║

╚═══════════════════╝

│ │

│ │

┌───────────┐

┌─────┴─────┐ (AppAction) -> MiddlewareInputAction? │ │

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┐ │Middleware │ { $0.case?.middlewareInputAction } │ │

Input Action │ Input │◀──────────────────────────────────────────────│ AppAction │

└ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘ │ Action │ KeyPath<AppAction, MiddlewareInputAction?> │ │

└─────┬─────┘ \AppAction.case?.middlewareInputAction │ │

└───────────┘

│ ┌─────┴─────┐

┌───────────┐ (MiddlewareOutputAction) -> AppAction │ │

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┐ │Middleware │ { AppAction.case($0) } │ │

Output Action │ Output │──────────────────────────────────────────────▶│ AppAction │

└ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘ │ Action │ AppAction.case │ │

└───────────┘ │ │

│ └─────┬─────┘

┌───────────┐

┌─────┴─────┐ (AppState) -> MiddlewareState │ │

┌ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┐ │Middleware │ { $0.middlewareState } │ │

State │ State │◀──────────────────────────────────────────────│ AppState │

└ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ┘ │ │ KeyPath<AppState, MiddlewareState> │ │

└─────┬─────┘ \AppState.middlewareState │ │

└───────────┘

│ │

Lifting Middleware using closures:

.lift(

inputAction: { (action: AppAction) -> MiddlewareInputAction? /* type 1 */ in

// prism3 has associated value of MiddlewareInputAction,

// and whole thing is Optional because Prism is always optional

action.prism1?.prism2?.prism3

},

outputAction: { (local: MiddlewareOutputAction /* type 2 */) -> AppAction in

// local is MiddlewareOutputAction,

// an associated value for .prism3

AppAction.prism1(.prism2(.prism3(local)))

},

state: { (state: AppState) -> MiddlewareState /* type 3 */ in

// property2: MiddlewareState

state.property1.property2

}

)

Steps:

- Start plugging the 3 types from MyMiddleware into the closure headers.

- For type 1, find a prism that resolves from AppAction into the matching type. BE SURE TO RUN SOURCERY AND HAVING ALL ENUM CASES COVERED BY PRISM

- For type 2, wrap it from inside to outside until you reach AppAction, in this example we wrap it (being “it” = local) in .prism3, which we wrap in .prism2, then .prism1 to finally reach AppAction.

- For type 3, find lenses (property getters) that resolve from AppState into the matching type.

Lifting Middleware using KeyPath:

.lift(

inputAction: \AppAction.prism1?.prism2?.prism3,

outputAction: Prism2.prism3,

state: \AppState.property1.property2

)

.lift(outputAction: Prism1.prism2)

.lift(outputAction: AppAction.prism1)

Steps:

- Start with the closure example above

- For inputAction, we can use KeyPath from

\AppActiontraversing the prism tree - For outputAction it’s NOT a KeyPath, but a wrapping. Because we can’t wrap more than 1 level at once, either we:

- use the closure version for this one

- lift level by level, from inside to outside, in that case follow the steps of wrapping local into Prism2 (case .prism3), then wrapping result into Prism1 (case .prism2), then wrapping result into AppAction (case .prism1)

- When it’s only 1 level, there’s nothing to worry about

- For state, we can use KeyPath from

\AppStatetraversing the properties.

Optional transformation

If some action is running through the store, some reducers and middlewares may opt for ignoring it. For example, if the action tree has nothing to do with that middleware or reducer. That’s why, every INCOMING action (InputAction for Middlewares and simply Action for Reducers) is a transformation from AppAction → Optional<Subset>. Returning nil means that the action will be ignored.

This is not true for the other direction, when actions are dispatched by Middlewares, they MUST become an AppAction, we can’t ignore what Middlewares have to say.

Direction of the arrows

Reducers receive actions (input action) and are able to read and write state.

Middlewares receive actions (input action), dispatch actions (output action) and only read the state (input state).

When lifting, we must keep that in mind because it defines the variance (covariant/contravariant) of the transformation, that is, map or contramap.

One special case is the State for reducer, because that requires a read and write access, in other words, you are given an inout Whole and a new value for Part, you use that new value to set the correct path inside the inout Whole. This is precisely what WritableKeyPaths are mean for, which we will see with more details now.

Use of KeyPaths

KeyPath is the same as Global -> Part transformation, where you give the description of the tree in the following way:

\Global.parent.part.

WritableKeyPath has similar usage syntax, but it’s much more powerful, allowing us to transform (Global, Part) -> Global, or (inout Global, Part) -> Void which is the same.

That said we need to understand that KeyPaths are only possible when the direction of the arrows comes from AppElement -> ReducerOrMiddlewareElement, that is:

Reducer:

- ReducerAction? ← AppAction // Keypath is possible

- ReducerState ←→ AppState // WritableKeyPath is possible

Middleware:

- MiddlewareInputAction? ← AppAction // KeyPath is possible

- MiddlewareOutputAction → AppAction // NOT POSSIBLE

- MiddlewareState ← AppState // KeyPath is possible

For the ReducerAction? ← AppAction and MiddlewareInputAction? ← AppAction we can use KeyPaths that resolve to Optional<ReducerOrMiddlewareAction>:

{ (globalAction: AppAction) -> ReducerOrMiddlewareAction? in

globalAction.parent?.reducerOrMiddlewareAction

}

// or

// KeyPath<AppAction, ReducerOrMiddlewareAction?>

\AppAction.parent?.reducerOrMiddlewareAction

For the ReducerState ←→ AppState and MiddlewareState ← AppState transformations, we can use similar syntax although the Reducer is inout (WritableKeyPath). That means our whole tree must be composed by var properties, not let. In this case, unless the Middleware or Reducer accepts Optional, the transformation should NOT be Optional.

{ (globalState: AppState) -> PartState in

globalState.something.thatsThePieceWeWant

}

{ (globalState: inout AppState, newValue: PartState) -> Void in

globalState.something.thatsThePieceWeWant = newValue

}

// or

// KeyPath<AppState, PartState> or WritableKeyPath<AppState, PartState>

\AppState.something.thatsThePieceWeWant // where:

// var something

// var thatsThePieceWeWant

For the MiddlewareOutputAction → AppAction we can’t use keypath, it doesn’t make sense, because the direction is the opposite of what we want. In that case we are not unwrapping/extracting the part from a global value, we were given a specific action from certain middleware and we need to wrap it into the AppAction. This can be achieved by two forms:

{ (middlewareAction: MiddlewareAction) -> AppAction in

AppAction.treeForMiddlewareAction(middlewareAction)

}

// or simply

AppAction.treeForMiddlewareAction // please notice, not KeyPath, it doesn't start by \

The short form, however, can’t traverse 2 levels at once:

{ (middlewareAction: MiddlewareAction) -> AppAction in

AppAction.firstLevel( FirstLevel.secondLevel(middlewareAction) )

}

// this will NOT compile (although a better Prism could solve that, probably):

AppAction.firstLevel.secondLevel

// You could try, however, to lift twice:

.lift(outputAction: FirstLevel.secondLevel) // Notice that first we wrap the middleware value in the second level

.lift(outputAction: AppAction.firstLevel) // And then we wrap the first level in the AppAction

// The order must be from inside to outside, always.

Identity, Ignore and Absurd

Void:

- when Middleware doesn’t need State, it can be Void

- lift Void using

ignore, which is{ (_: Anything) -> Void in }

Never:

- when Middleware doesn’t need to dispatch actions, it can be Never

- lift Never using

absurd, which is{ (never: Never) -> Anything in }

Identity:

- when some parts of your lift should be unchanged because they are already in the expected type

- lift that using

identity, which is{ $0 }

Theory behind: Void and Never are dual:

- Anything can become Void (terminal object)

- Never (initial object) can become Anything

- Void has 1 instance possible (it’s a singleton)

- Never has 0 instances possible

- Because nobody can give you Never, you can promise Anything as a challenge. That’s why function is called absurd, it’s impossible to call it.

Xcode Snippets:

// Reducer expanded

.lift(

actionGetter: { (action: AppAction) -> <#LocalAction#>? in action.<#something?.child#> },

stateGetter: { (state: AppState) -> <#LocalState#> in state.<#something.child#> },

stateSetter: { (state: inout AppState, newValue: <#LocalState#>) -> Void in state.<#something.child#> = newValue }

)

// Reducer KeyPath:

.lift(

action: \AppAction.<#something?.child#>,

state: \AppState.<#something.child#>

)

// Middleware expanded

.lift(

inputAction: { (action: AppAction) -> <#LocalAction#>? in action.<#something?.child#> },

outputAction: { (local: <#LocalAction#>) -> AppAction in AppAction.<#something(.child(local))#> },

state: { (state: AppState) -> <#LocalState#> in state.<#something.child#> }

)

// Middleware KeyPath

.lift(

inputAction: \AppAction.<#local#>,

outputAction: AppAction.<#local#>, // not more than 1 level

state: \AppState.<#local#>

)

Architecture